How a handful of Toronto businessmen got their way on bike lanes province-wide

Jack Hauen, The Trillium, November 14, 2024

Jack Hauen, The Trillium, November 14, 2024

Last fall, a group of local business owners launched a petition against recently installed bike lanes on a section of Bloor Street in Toronto.

A year later, Premier Doug Ford announced his intention to rip up that bike lane, along with two others.

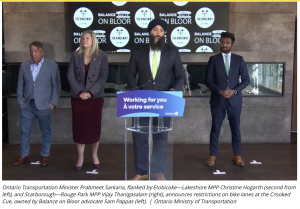

Days before the premier’s announcement, Ford’s transportation minister spoke at a restaurant owned by a member of the group — Balance on Bloor — to announce heavy provincewide restrictions on new bike lanes, repeating several of the group’s talking points about their effects on traffic and businesses.

Balance on Bloor’s founder, Cody MacRae, said it’s a “non-partisan group of local volunteers from across the political spectrum.” Yet the group’s success in winning the most powerful man in Ontario to its cause would be the envy of any grassroots activist.

How did a handful of Toronto business owners manage to parlay their gripe with local bike lanes into provincial legislation?

Balance on Bloor includes PC donors, former candidate

Balance on Bloor has a well-connected board of directors in Sam Pappas, Simon Nyilassy, Ron Sedran and the petition starter, MacRae.

Nyilassy was a Progressive Conservative candidate in 2011. He’s a longtime real estate executive and the founder and CEO of Marigold & Associates Inc., a real estate investment firm. Someone with Nyilassy’s name has donated a total of $18,827 to the PC Party since 2014, including a $1,500 donation last month.

Sedran is a managing director at Canaccord Genuity, a financial services company. His name matches that of a PC donor who gave a total of $5,935 to the party via a pair of donations in 2015 and 2018.

Pappas is the owner of The Crooked Cue, an Etobicoke bar known as a gathering place for bike lane opponents — and where Transportation Minister Prabmeet Sarkaria made the announcement restricting new bike lanes on Oct. 15.

MacRae is a real estate agent who boasts of “an extensive network across the political sphere,” though he stressed his group’s nonpartisanship.

“While the strength and passion of our community are central to our efforts, we recognize that this issue extends well beyond Bloor Street and the GTA—many communities across Ontario are facing similar challenges due to ill-conceived, unsafe and poorly implemented bike lanes,” reads a statement MacRae sent to The Trillium.

“Though a variety of factors influenced the provincial government’s decision to table Bill [212], we believe the united voices of residents from towns and neighbourhoods throughout the province played a decisive role,” it reads, referring to the legislation that would remove and restrict bike lanes.

“Together, we remain optimistic and hopeful for meaningful change.”

Nyilassy declined an interview, pointing to MacRae’s statement. Sedran did not respond to several requests for comment.

How it came together

Pappas said his group has been “advocating very hard” against the Etobicoke portion of the bike lane with both the City of Toronto and the provincial government.

“We went to everybody,” he said. “But initially, nobody really responded, to be honest.”

Pappas said he had a productive meeting with Toronto Mayor Olivia Chow, but nothing came of it. Chow has pushed back on the province’s move to bigfoot her city.

Eventually, Etobicoke—Lakeshore MPP Christine Hogarth, another opponent of the Bloor West bike lane, reached out, Pappas said. Hogarth, whose riding encompasses the Etobicoke portion of the lane, met with MacRae and Sedran last December on the topic.

“From there, it kind of took steam,” Pappas said.

He said he didn’t hear much from the province until CBC broke the story in September. That’s when Hogarth got back in touch, he said. Hogarth did not respond to a request for comment.

“Christine Hogarth reached out and said, ‘Would you mind if somebody got a hold of you from the (Ministry of Transportation)?’ and I said, ‘Sure,’ right? And away we went,” Pappas said.

“I mean, I guess the provincial government knew how hard Balance on Bloor was working on this issue,” he said. “So when I got contacted by the provincial government to do the press conference, I was more than happy.”

“The provincial government’s the only one that could do anything, so obviously I’m going to listen to them,” he added.

Speaking at the announcement last month, Sarkaria said the Crooked Cue was “one of the best places in the city to hang out and play some pool,” calling Pappas “a tireless advocate, not only for this community, but for small businesses across this province.”

Hogarth has held two election night victory parties at the Crooked Cue. But Pappas said he’s hosted scores of politicians of all political stripes over his 30-plus years in business.

Ford and his late brother, Rob, “were there all the time,” he said. Former governor general Adrienne Clarkson held a book signing there. And now-mayor Chow and the late Jack Layton played pool there during their time on city council.

“I don’t actually get involved or support anybody. I just provide the venue,” Pappas said.

Still, while it’s not strange for bike lanes to receive pushback, it’s unusual for the provincial government to intervene on such a local issue, said Albert Koehl, a founder of the Toronto Community Bikeways Coalition.

“Obviously, they’ve got the premier’s ear,” he said.

“The pattern you’re seeing from the provincial level is the average person gets bribes — you know, fantastical proposals like the 401 tunnel … whereas the wealthy are the ones that get action,” he said.

Outrage at bike lanes in Ford Nation

The fight for bike lanes on Bloor Street has spanned decades. They became a reality in 2016, when the City of Toronto installed them in Old Toronto, from Avenue Road to Shaw Street. Four years later, they extended west, just past High Park, to Runnymede Avenue.

In 2023, the city stretched them to Aberfoyle Crescent in Etobicoke. The next year: one more kilometre to link up with existing lanes near Kipling Avenue.

That final push over the last couple of years royally irked some residents.

A petition started by MacRae on Oct. 23, 2023 racked up thousands of signatures stressing “the need for Bloor Street to retain two lanes of traffic in each direction.”

MacRae cited “scarce cyclist usage,” “reduction in traffic flow” and “loss of business revenue” — all reasons the Ford government would go on to cite in its push to restrict bike lanes.

Eight days after the petition started, Ford weighed in, calling on Toronto Mayor Chow to “get rid of those bike lanes on Bloor in Etobicoke.”

“I think we see one bicycle come through there every single year, with thousands of cars. I know the businesses are just losing their hair over having those bike lanes in Etobicoke on Bloor Street,” said the premier, who is also the MPP for Etobicoke North.

(A few days later, a bike counter at Bloor Street and Keele Street, about three kilometres east of Etobicoke, showed 415 cyclists had used the lane as of that afternoon, and 189,587 since the machine was installed that summer).

Government comms mirror group’s advocacy

Since Ford’s initial salvo against the bike lanes last year, several of Balance on Bloor’s favourite talking points have made their way into government communications.

An October op-ed from a Balance on Bloor member said the group counted 10 snowplows and nine cyclists one day this past winter.

“In winter, bike lanes see more snowplows than cyclists,” Sarkaria said in a video posted to X last week.

The group often points to alleged delays in emergency response times.

“I don’t see how they’re gonna be able to pass that area at all,” Pappas said of emergency vehicles at a city meeting on the bike lanes in June 2023. “If you come through right now during rush hour, anytime between 3 and 6 o’clock, it’s already bumper-to-bumper.”

Ford has said that first responders are “pulling their hair out” over delays caused by bike lanes, calling them “an absolute disaster, it’s a nightmare.”

According to Toronto’s deputy fire chief, however, response times have improved since the Bloor bike lanes were installed.

Balance on Bloor has frustrated cycling advocates, some of whom accuse the group of distorting the facts.

“At the end of the day, I don’t think the City of Toronto has any vested interest in presenting untrue data,” Cycle Toronto executive director Michael Longfield said. “And so when the counter-argument is, ‘Well, we’ve done our own research,’ it makes it … hard to have a conversation about.”

Perhaps the main complaint of Balance on Bloor is the lack of cyclists using the bike lanes, while cars are often stuck behind other cars.

“Many residents and businesses along Bloor St. have observed a limited number of cyclists using the designated lanes,” the petition reads.

The Ford government has claimed that bike lanes cause congestion, while only 1.2 per cent of Torontonians cycle to work, which is untrue.

“There is no major study in the world that says that bikeways are a leading cause of congestion, and most will even suggest that they’re a way to improve traffic and congestion,” Longfield said.

“And again, if we can’t agree on these facts, it does make having these conversations very challenging, and I think it can split things into a kind of culture war that I don’t think benefits anybody.”

The group has also complained about the bike lanes’ effects on businesses — which are “losing their hair,” as the premier put it.

Further east on Bloor, the local BIA told the province to leave the bike lane alone, saying “the sky didn’t fall, and sales went up.”

Decades of studies indicate bike lanes tend to benefit businesses.

In response to questions for this story, Sarkaria’s office sent a statement that reiterated the misleading 1.2 per cent figure and touted its “common-sense approach to bike lanes.”

‘Hardcore cyclists’

Balance on Bloor members say they’re pro-bike lane — just not in their backyards.

“I’m a cyclist myself, recreationally, for that matter. But our board of directors (is) filled with some more hardcore cyclists,” MacRae told CBC last month.

“We support safe biking infrastructure and bike lanes where they make sense. But they don’t make sense in our community.”

Sarkaria agreed in an op-ed last month that “we need bike lanes — where they make sense.” That means “on side streets or in quieter neighbourhoods” instead of “major thoroughfares like … Bloor Street West in Toronto,” he wrote.

Touting one’s cycling bona fides has become a tell, Koehl said.

“It’s sort of a joke among road safety advocates,” he said. “If you hear someone preface their comments with, ‘I love cycling,’ we all know what’s coming next: ‘but not here.'”

Bike lanes encourage more people to bike instead of driving — not just hardcore cyclists who might already be comfortable riding next to cars, Longfield said.

“The purpose of these bikeways, and the bikeways on Bloor in particular, is because most people consistently say that for riding a bike to be a convenient and safe option for them, they need a network of safe and connected bikeways,” he said.

City of Toronto staff found that tearing out the three planned bike lanes in Toronto will cost $48 million, dramatically increase travel times during construction and will not deliver much time savings for commuters when the lanes are out. And the city will be out the $27 million it cost to install the lanes in the first place.

Koehl bemoaned the decades of study and debate on the Bloor bike lanes, potentially undone by a premier based on “what he’s heard on the street.”

“But we know it’s a wedge issue, right?” he said. “(Ford) obviously hates the bike lane, but he’s also clearly come to the conclusion that this makes a really good election issue, despite the fact that people will die.”

Editor’s note: Cody MacRae’s statements in this article were updated on Nov. 14 at 2:18 p.m.