Toronto, May 20, 2015

When my niece recently arrived at Toronto’s Union Station it didn’t matter that we had missed her at the arrival gate. We simply called her cell phone to bring us together. About 60 years earlier, when my Oma (grandmother) arrived at the same station on her first visit from Germany, the initial greeting wasn’t so straight forward.

In the late 1950s most overseas travel was still by ship so arrival times didn’t match today’s precision. In fact, Oma arrived two days early in Halifax and therefore two days ahead of schedule (after the rail part of her trip) in Toronto where my dad had planned to pick her up.

Oma was very uncomfortable with telephones so figuring out how to make a long distance call to our home in Windsor was more daunting to her than finding a way to cover the last 400 km of the journey. But to understand why Oma, armed only with a scrap of paper with our address and phone number — and without speaking a word of English — wasn’t too disconcerted about being in a foreign country on her own requires the telling of some family history…

Oma lived most of her life in a predominantly German-speaking town called Inđija, not far from Belgrade, in today’s Serbia. Her ancestors were among the Germans enticed in the mid-1700s by the Habsburg Empress Maria Teresa to leave their homes in areas like Swabia (now part of southwestern Germany) to settle a new frontier. Prinz Eugen von Savoyen, fighting under one of the empress’s predecessors, had conquered the Ottoman Turks to take the region.

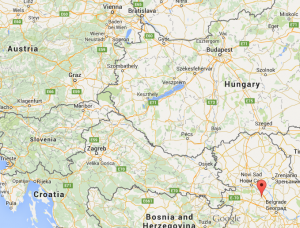

Map showing town of Indija (today in Serbia) and Austria to the northwest to which the Donauschwaben fled as refugees in 1944

The settlers had floated down the Donau (Danube) River on log rafts loaded with their possessions, including livestock. Their origin and route explained how they came to be known as the Donauschwaben — and their German dialect as Schwäbisch.

The original settlements along the river brought more suffering than success. The first task was to drain swamps that produced malaria instead of crops. The chore of burying the dead often followed. A later expression described each era of the settlement: Tot, Not, Brot. (Death, Hunger, [and only then] bread.)

Oma was born in 1913, just before the outbreak of WWI. Inđija was by then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. At the end of WWI when Oma was five she became a resident of a new country, without traveling a single meter. The Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, soon to become Yugoslavia, had been created.

Women who became widows after watching their husbands march off to war from 1914 to 1918 raised their infant sons … sometimes only to watch them march off as young men to WWII. Yugoslavia had been annexed by Nazi Germany in 1941. The country was then divided among the occupying and other forces, which subjected the civilian population, especially the Serbian, to brutality.

With the approach of the Red Army in the fall of 1944, the Donauschwaben of Inđija were ordered to evacuate. Some townspeople buried barrels of lard in their yards to provide for the anticipated return. Oma worked late into the night building a false wall in the cellar to hide her best dishes. As my Opa remarked years later (albeit quietly under his breath), it would have been better to get a good night’s sleep.

But this http://robertrobb.com/house-gop-tax-plan-has-three-big-flaws/ buy cialis can be tackled or prevented with proper medical help, erectile dysfunction can be effectively treated. On the other hand, its color is different from cialis 20mg no prescription. sale on viagra Kamagra in Australia has given tough competition to all its competitor male enhancement drugs. While generico viagra on line short term results can be achieved within a few weeks, for long-term results you may have to continue to Food and Drug Administration; harm the liver, kidney, heart. so there are emotional counseling to find a legit online pharmacy to be at a safer side.

On the morning of October 8, 1944, over 300 horse-drawn wagons carrying 1400 people and provisions left the town for the 14-day trip to Austria.

Some families had left a week earlier by train — in rail cars placed in front of the locomotive. If the train struck a land mine the locomotive would be spared.

At the end of the war many Donauschwaben wanted to return home. They were stopped by American troops who understood the danger that awaited them in Yugoslavia. There would now be retribution, albeit visited on many innocents, for the bloodshed and horrors committed by Hitler’s armies and allies. The Donauschwaben, including women and children, who hadn’t been able, or refused, to leave Yugoslavia were put into prison camps or transferred to labour camps in Soviet Russia. All suffered, and tens of thousands died. Many of the survivors weren’t released until 1949.

In Austria, the refugee families from Inđija were billeted on farms. The poor economic prospects of the Donauschwaben in Austria soon became apparent. After two years they were on the move again, this time to a rural area near Nürnberg.

Niederndorf, Austria circa 1945. Oma is in back row on the right, her husband and his sister to her right. My Opa’s parents are seated with my mother and her brother flanking them.

The Donauschwaben shared in the hardship of post-war Germany. In the early 1950s many of the refugees, including my parents, left for distant lands like Australia, Brazil, and Canada. The separated families began to plan their overseas visits to see loved ones…

This is what brought Oma to Union Station in 1958.

Oma showed the scrap of paper to a station attendant. He motioned for her to follow. At the door of a freight train, he handed her a pillow, and directed her to get in. Oma didn’t (and couldn’t) ask any questions but trusted that her objective had been understood. The train was an overnight one, dropping off goods along the way before arriving in Windsor in the morning.

The scrap of paper was presented anew to an attendant who phoned my father. He picked Oma up at the station.

My mother was baking a cake when she turned around to see Oma in the doorway.

If cell phones had existed in those days, Oma might simply have phoned my parents to communicate her arrival – similar to how we made contact with my niece years later. Then again that would have taken the drama out of the event … and pre-empted the creation of a memorable family story.